|

If you would like to be the kind of person who never stops learning, the best advice I can give you is to become a high school teacher. Some days, you learn just where your limits are and then promptly go right past them, until you're saying words you know you're going to regret. (My personal favorite: "Of all the things you can choose to be in this world, why would you choose to be an asshole?") Some days, you learn about Classical Conservatism from no less an authority than Klemens von Metternich himself. And some days, you see the future, and you learn that humanity might still be OK.

All three of those things happened today. Two of them have the potential to be blog posts (I plead the Fifth on that first one), but it's International Women's Day, so I want to say a few brief words about my Women's Studies class. (Yes, I'm a guy. Yes, I teach Women's Studies. Yes, it's a long story. Suffice it to say that the only reason I teach it is because three little sisters asked me to.) We've been moving through the herstory of women's rights in America, from the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, through the long trials of the fight for suffrage, with stops in both World Wars and then on into the 1960's. We're now firmly entrenched in Second Wave Feminism. We've read from The Feminine Mystique. We've had group discussions on a host of poems and articles, and beginning at the tail end of last week, we began creating the Feminism Hall of Fame. It's a simple exercise, based on the plaques from the Baseball Hall of Fame, which have an image of the player, their years in the Major Leagues, and their accomplishments. I altered it so that the students were assigned one Second Wave Feminist and needed to include her picture (preferably from the time period), her date of birth (and, if applicable, death), and then a 300-500 word essay about her accomplishments, all of which should fit on an 11x17 poster. We created the posters last week, and I hung them up outside of my room today. During class today, we did a Gallery Walk. If you're unfamiliar, you simply display a number of items (in this case, the posters), and then have the students pretend each is an exhibit in an art gallery, and they walk from one to the next and view the exhibits. I asked them to view at least a dozen posters outside of their own, write down a few pieces of pertinent info about the feminist covered in that poster, and then write a brief paragraph about the experience. I reminded them that due to spacing and other issues, the posters were in the hall, and reminded them that other classes were in session in other rooms, and then I turned them loose to work on their assignment. I've done this exercise before. I almost always have to redirect--not a lot, but on occasion--or point out that there's no waiting at this exhibit while six friends all gather at that one. I didn't have to do that today; not once. This is the first time I've done the lesson in a COVID world, also. Were we always socially distanced? No. Were we ever within six feet of someone else for 15 minutes? Also no. And let me tell you: you could have heard a pin drop. Every student was reading the essays, looking at the pictures, finding out who was still alive, or expressing dismay that someone else had passed away so recently. There were more than a few comments to me: "She was in the movie!" "I remember her!" "I didn't know she was a member of Congress!" There are moments, being a teacher, when the lesson goes well, or when both you and the students are having fun, or when you get that feeling of, "Hey, it's possible I know what I'm doing!" This was all of those things, and on top of that, it was beautiful. About twenty little sisters (and a couple of fine young feminist little brothers) spent forty minutes in silence, observing positive female role models who, once upon a time, changed the world. The National Women's Hall of Fame is in Seneca Falls, New York, where way back in 1848 the Declaration of Sentiments was both presented and signed. But for three-quarters of an hour today, the Feminist Hall of Fame was outside my classroom, and its opening was a smashing success. Happy International Women's Day, one and all. Humanity might still be OK.

2 Comments

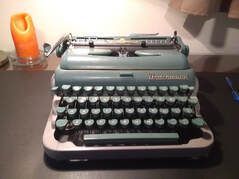

Anyone who knows me knows I don't need another typewriter. I'm coming up on 40 of them now. The difference between owning a typewriter and having a typewriter collection isn't a large difference; both of these things give me membership in a shrinking minority of people. A typewriter collection means I talk about Tom Hanks more than other people do; when you're not a typewriter collector, one of the few things you know about typewriter collections is that Tom Hanks has one. I enjoy Mr. Hanks' work and I'm envious of his collection, so speaking about him is not something I view as a hardship, but it doesn't always go anywhere -- we mention the collection and we each choose our favorite movie, and then we have nothing else to talk about.

The thing is, I'm not really a typewriter collector, either. I'm a writer, or I try to be. I don't have a great deal of interest in antique and collectible typewriters; I have interest in typewriters that can be used. I own multiple typewriters because beyond the basics, I know very little about typewriter repair, and I don't want to be caught without a working typewriter. I even have multiples of the same typewriter for this very reason (because honestly; can anyone kill a mid-50's Smith-Corona?). I enjoy knowing I can keep typing for many days to come, but others find my collection mildly annoying. My wife sometimes wishes I collected spoons or thimbles or something--you know, the type of thing where the entire collection might fit in a single drawer. Still, this post is not really about typewriters, nor is it about the perils and pleasures of typewriter collecting. This post is about Fate. It happened like this. Earlier this week, I had a birthday. My father-in-law sent me a card with a check. My in-laws have been sending me checks on my birthday every year since I married their daughter; Mom started it, and when she passed Dad continued it. So I had this check from Dad that I needed to cash. I also have a dear friend, and this dear friend of mine and I exchange letters. I have shared the dorky joy of owning a typewriter with this friend, and so we type letters back and forth to each other, as we only actually see one another four or five times a year. My friend sent me a lovely letter that arrived on my birthday, and yesterday I typed my reply and sealed it. But the letter needed a stamp, and I didn't have any fun stamps. I had stamps; I just didn't have any fun ones. This is one of my best friends in the world, you understand, and the lack of fun stamps caused a minor moral dilemma. Did I really want to use an un-fun stamp for one of my best friends? Was I supposed to use the same stamps for my dear friend that I use when I pay my bills? I didn't think so. I had errands to do yesterday. I had told my wife I could take care of the grocery shopping. I needed to put gas in my car. I needed to cash that check I got from Dad. So I figured I would just add to the list of errands and go to the Post Office and buy some fun stamps and mail the letter to my friend, as well. All told, that would only add about ten minutes to my errands (it's a pretty small town, where I live). So I got the gas and I cashed the check, and then I headed across town to the Post Office. (One should always save grocery shopping for last, so the frozen items don't thaw too much in the car.) I bought 20 stamps celebrating the Lunar New Year and the Year of the Ox, and I used one of them to mail the letter, and that was that. Except it wasn't. Because I had taken ten minutes to get to the Post Office, my route back to the grocery store had been altered. Not by much -- again, it's a pretty small town -- but enough that my return took me past a St. Vincent de Paul store. I thought to myself, "When was the last time I had been inside this St. Vinnie's?" and I could not recall, but I did remember that the last time I had been inside, they had had a typewriter near the exit. I had time, so I pulled in the parking lot and walked inside, and I didn't find anything I really needed. Still, I walked toward the exit and checked the shelves, and there I found a late-50's Triumph De-Jur Perfekt. This is not the most common typewriter to find, but there it was, a portable in a hardshell case that even had the original brushes and cleaning cloth. Its two-toned color practically gleamed beneath the fickle St. Vinnie's fluorescent lighting. It had a piece of paper in it, so I tried it out a little, and the German engineering (West German, at that time) was evident from the first. I don't need another typewriter. "You're buying that?" asked the lady at the counter as I plopped the case near the register. "I just put that out ten minutes ago. But I don't know if I can sell it to you; our credit/debit system is down right now." If you're following along at home, here's a brief recap of where we are right now:

Anyone who knows me knows I don't need another typewriter. But anyone who knows me also knows that when Fate slaps me upside the head, I pay attention. Welcome to the collection, Beautiful.  It wasn’t supposed to go this way. When I last posted on this blog, I had a plan for what came next, but that plan got cast aside due to my students. Honestly, it’s OK when things get cast aside due to students—a lot of learning can happen out there in the Land of Unexpected—but my plan got derailed, and it’s kept me from putting together the sequel to my last post for longer than I anticipated. We started Second Semester recently. My Women’s Studies classes are only a semester long, so I bid adieu to one group and welcomed another. It’s hokey, but in each of my classes I ask students to fill out a “Getting to Know You” sheet. It’s not much—just a few questions that help me 1) learn their names and a few things to associate with them, and 2) learn the names of bands they listen to, so when we talk music I seem cooler than I am. As part of this exercise, I ask students to write down one question they would like to ask me, and then I answer that question, so they can get to know me a little bit, too. The questions are usually pretty innocent, but this time, one of the young ladies in the class threw down the gauntlet, and asked, “What do you think of the Black Lives Matter movement?” By this point, most of the students in my school district are aware of a portion of what went on with me this year. At the beginning of the year, I hung up a Black Lives Matter flag in my classroom. I was subsequently ordered to take it down, and I took it down. That’s the portion of the story they know, the same portion I wrote about in the previous blog post. The rest of it goes like this. I was ordered to take the flag down, and I did. I was informed that the reason it had to come down was not because whoever had given the order to take it down had anything against black people, but rather because I had—and this quote is accurate—"failed to show both sides” of the issue. Of course, I had questions, the most prominent one being, “What the fuck? ‘Both sides’?” I pondered what that meant. Did that mean I could keep the Black Lives Matter flag on the wall, as long as I added a white robe and a hood to a different spot on the wall? Whoever gave the order for the flag to come down didn’t know this, but I used to be a drama major. I wasn’t very good at it, but I know a lot of people who were, and who went on to careers within the arts. I know at least three people with access to a university or semi-professional costume shop, and I could probably get my hands on a white robe and hood; I was willing to do that just to see if that was really what the Powers-That-Be wanted. I calmed down, mostly because I really don’t want anything to do with the KKK hanging in my classroom (or anywhere else near me, for that matter). Instead, I filled out a form that allowed me to speak in front of the School Board and on a Monday night in late September of last year, I delivered what I thought was a pretty good speech. I mentioned the ‘both sides’ thing and told them I didn’t know what might best convey the notion that black lives DON’T matter, and I also told them that I chose to believe that showing ‘both sides’ was not, in fact, what they wanted. I talked about the School Mission Statement and whether we were living it, I spoke about my own whiteness and about liberty and justice for all… Honestly, it really wasn’t a bad speech. Well, I didn’t think so, anyway. Public comment is just that—comment, and not conversation—so when I was finished speaking I left the meeting and went home. I don’t know what I expected to happen; I suppose I hoped that those who had decided to make me take the flag down might reconsider. Instead, shortly thereafter I had a letter placed in my employee file. I had to attend a meeting where I was informed I was being written up for a fire code violation because my classroom walls were “cluttered” with flags and maps. I was being written up for not sharing lesson plans with my building principal indicating just how a Black Lives Matter flag might fit with my classroom curriculum. I was written up for failing to address my concerns through proper channels, and asked to reconsider how much I posted on social media. And I was reminded that I had an obligation as a teacher to teach ALL students within my classroom. It was a non-disciplinary letter, at least. When I asked what the alternative might be, I was told the alternative was that I would be “walked outside in the rain.” I still remember that line, just as I remember looking out the window to check how much it was raining (quite a bit). I even remember thinking to myself, “Oh, shit: do I have an umbrella in my room?” I was told I could write a reply to the letter. I was told that if I felt the need to resign my position I would not need to pay the $1500.00 required by the Employee Handbook to break my contract. I replied to the letter. I did not resign. I had other options. Some people I knew watched the live stream of the school board meeting and heard the speech I gave, and they know some people, and before too long, I had been invited by two competing television stations to be interviewed about the incident. Everyone I corresponded with at both stations was thoroughly professional and quite pleasant, but while I appreciated their interest, I turned them down. I turned them down because suddenly the whole situation seemed to be about ME. I had been forced to take down MY flag, and wasn’t it all an injustice to ME, and so on. I’m not saying that’s even how the people at the television stations felt, I’m just saying that’s how it felt to ME, and that didn’t feel right. I happened to agree—what occurred had been an injustice to me, in my opinion—but what about the ongoing injustice perpetuated against black people? Wasn’t that the point? Going on TV felt self-aggrandizing. It felt like I would end up as the focus, and I didn’t want to be the focus. I wanted the Black Lives Matter movement to be the focus. I felt like my own tiny issue was getting conflated with the much larger issue of the Black Lives Matter movement, and I didn’t think that was appropriate. You may think everything that happened to me was perfectly appropriate and I deserved every bit of it. You might think the opposite. Whatever you think is entirely up to you. I will say that I have spent the past several months teaching on eggshells, afraid that whatever else I might say in support of racial justice or even about black people in history might be enough to get me “walked outside in the rain.” It’s Black History Month. I’m about six class periods away from starting our study of the Civil Rights Movement, and I don’t even really know if I’m allowed to talk about it. What happens when I say Malcolm X may have made some good points? What happens when we read the Black Panthers manifesto? I don’t know, but I keep an umbrella in my classroom. And all of that was going through my head when I moved from one piece of paper to the next and read a question one of my new students wrote: “What do you think of the Black Lives Matter movement?” I don’t know if I was supposed to talk about it. But a student in my class had a question, and when the question got asked, I answered it. While I didn’t record my response, I recall saying something like this: “Most of you know I had a Black Lives Matter flag on the wall this year and I was asked to take it down, and that has made this a pretty hard year for me. I put it up because I believe in the words: I believe black lives matter. They have value. I’ve had a Pride flag up on my classroom walls for the past five years, and when people ask me why I have it, I tell them that a lot of students come into this classroom, and some of them are gay. And those gay students—and trans students, and bi students—deserve to be valued and respected and appreciated as much as the straight students who come into this classroom. I put up the Black Lives Matter flag because I believe Black students—and Hispanic students, and Native students, and Asian students—deserve to be valued and appreciated every bit as much as the White students who come into this classroom. And I believe that, whether the flag is on the wall or not.” I thought that was an OK thing to say. Some of the students agreed; a couple of them even applauded, which was nice of them. But here I am, doing the same thing I said I wanted to avoid; I’m making this post about ME. You want to know about me? I’m a middle-aged white guy. I have no business being thought of as some kind of champion of the Black Lives Matter movement; I haven’t gone to a rally, I haven’t taken part in a march, I haven’t sent any money, and I’m not black. I hope I’m an ally to the Black Lives Matter movement, but I could easily understand if after reading this post, people might not consider me to even be that. Because if you really want to know about me, then you should remember that I caved. I was told to take down the flag, and I took it down. I tried to change some people’s minds about that, but when I failed, I didn’t try again. I could have taken the fight to TV, but I turned down the interviews. I could have resigned to show my commitment to the principle, but I still show up each day and go to work in a place that will not tolerate having a Black Lives Matter flag on the walls of a U.S. History classroom. Which is to say, I showed a commitment to the cause of racial justice until it became personally inconvenient for me. That’s not “woke.” That’s white privilege. As I said earlier, there’s a lot that can be learned in the Land of Unexpected, and this 50+-year-old white guy learned a lot that day. I thank that young person in my Women’s Studies class for helping me learn I am still a long way away from the kind of man I wish to be. Maybe someday I’ll be “woke,” but not until after a lot more work.  A nametag I would not feel comfortable wearing, at present. A nametag I would not feel comfortable wearing, at present. A few weeks back, a fellow teacher phoned my room during a passing period to ask about some headwear one of our students had on. Our school has a hat policy (not allowed). Our school has a far more nebulous policy regarding head coverings. I had seen this student in a previous hour, and I had witnessed the headwear. In my day, it would have been called a do rag, but my day was many days ago, so I have no idea if that’s what it would be called today. When I saw it in my classroom, I let it go. My colleague, however, had asked the student about it, who of course responded with something along the lines of, “Well, I just got out of Brehm’s class, and he didn’t say anything.” I explained my reasoning to my colleague, but I won’t explain it here, because it’s always possible the student in question might read this and I have no wish to call out or embarrass that young person; their story is the introduction to what follows, but it isn’t the point of this post. The point is what happened at the end of the phone conversation with my colleague. This was a few weeks ago, so I’m certain I’m paraphrasing, but she said something close to, “Well, I thought I would ask you, since you seem to be the most ‘woke’ person who works here.” While it might seem paradoxical, to me ‘woke’ has one notable thing in common with the word ‘racist,’ and that is, I don’t think you get to decide for yourself if the term applies to you. Someone else gets to determine if you happen to be racist, and someone else gets to decide if you’re woke. But that one word – ‘woke’ – changed the entire tenor of the conversation. Instead of talking about a do rag (or whatever it’s called), we were suddenly talking about race. (We interrupt this post to consult the internet, to ascertain whether my line of thinking is at least a little bit correct. There, I learn the article of clothing is indeed still called a do rag, or a do-rag, or a durag, which came from dew-rag, where ‘dew’ was a euphemism for sweat. Also called a wave cap, it is designed to accelerate the development of waves or dreadlocks, or to keep waves or braids from shifting while asleep. And yes—the point I really wanted to make sure I made correctly—the garment is traditionally associated with African-Americans, with a history going back to slavery, through the Harlem Renaissance and the Black Power movement, and into today. Even history teachers should double-check their history, from time to time.) I am white. The colleague on the other end of the phone that day is also white. The student wearing the head covering in question that day is also white. But my colleague’s use of the word ‘woke’ got me thinking. Would I have asked a black student to remove a do rag? No. I never would. So did I act correctly in also not asking a white student to remove it, and therefore made a good decision? Or, had I allowed a young person to engage (perhaps even unknowingly) in cultural appropriation, and therefore made a poor decision? Weeks later, I still don’t know the answer to that question. But I do know how I felt at the end of that phone call, because this marked the first time someone else had applied the word ‘woke’ to me. I won’t lie; I felt complimented. I felt good about that. When it comes to race, I would like to be as ‘woke’ as I can be. But the feeling didn’t last, because I don’t believe I deserve the term. I don’t think of myself as woke. At best, I’m still trying to wake up. I work pretty hard to include race relations as an essential part of my U.S. History curriculum, and I hope I do a passable job. At the Freshman level, our portion of U.S. History basically covers the 1890’s to Whatever-We-Get-To, which in some years has been Nixon and in some years has been Trump and in some years has fallen in between. But my students cover Plessy v. Ferguson. They’re tested on Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois and Ida Wells. We go over the Great Migration and Black Wall Street and race riots and the KKK in the 1920’s. We talk about sundown towns and the Tuskegee Airmen, about the Democrat/Dixiecrat divide of 1948. By this point in the year, I am routinely about two weeks ahead of my colleague who also teaches U.S. History, and when we chat about it, he’s not worried, because we both know he’ll catch up due to the time I take going through the Civil Rights Movement. I am a white educator attempting to do a passable job of teaching black history; I can always do better, but I promise you, I try. As someone who tries, I have kept my eye on the Black Lives Matter movement for some time now; basically since its inception following the homicide of Trayvon Martin. Since then I’ve learned other names, of course. Eric Garner. Michael Brown. Tamir Rice. Walter Scott. Alton Sterling. Philando Castile. Breonna Taylor. George Floyd. Jacob Blake. And I am wise enough to know there are many other names that I have not learned. For many years now, I have placed a Pride flag on my classroom wall. It heartens some people, and offends others, and sometimes I am asked why I have it up there at all. My response is always the same: “A lot of students come into this classroom, and some of them are gay.” A lot of students come into my room, and some of them are black, but I never put a Black Lives Matter flag on my wall, until this year. For the record, it lasted almost a full month before I was ordered to take it down. And for the record, when I was ordered to take it down, I took it down. Monday is February 1, the beginning of Black History Month. The week of February 1-5 has been designated by the National Education Association (NEA) as “Black Lives Matter at School” week, designed to explore topics of racial equity in education. On top of all that, a few weeks ago a colleague called me ‘woke’ when I am unworthy of the title. So for a little while, this blog will be turned over to issues of race. Trust me, I know, I get it—we don’t need another white guy trying to teach us about race in America, so that’s not what I’m trying to do. Instead, I’m trying to tell my side of one particular story. It’s a story where black lives matter, and where I am absolutely not the hero. Perhaps it’s a mea culpa regarding the way I wish things would have gone. While ultimately, I still think it’s for someone else to decide, maybe—just maybe—I might be waking up.  They say money can’t buy happiness, but some of us at work decided to play the lottery anyway. As the recent Mega Millions jackpot climbed toward the billion-dollar mark, the gentleman in the classroom next to mine suggested we get a group together. I had organized a few such groups in past school years, and so when asked, I agreed to take it on again. I had no plans to do such a thing until I was asked, simply because when you start a lottery group at work, it creates pressure. Some people absolutely want to get involved, but others only get involved because of that pressure. Everyone knows the odds of winning the lottery are horrible, but everyone knows that—every once in a while—people win the lottery. Therefore some members of the group don’t really want to be there at all, but they really don’t want to be the poor soul who has to come to work the next day after 30 people in the building combine to win the lottery. So a band of enthusiastic participants and a band of reticent participants with FOMO came together, and we collected over $200. That bought us over a hundred lottery tickets, and when the drawing came, we WON! . . . a grand total of $18. But here’s the thing: no one won the jackpot that night. Now all of us had FOMO. Was I supposed to just cash out and buy doughnuts for the break room when there was still $840 million out there? Of course not, so I emailed everyone in our group and told them I would use the $18 to get nine more tickets for the next drawing. Then, people starting coming in. As long as I was getting some tickets, I should get a few more, and next thing I knew I was collecting money all over again. This time, the group widened to include a few more members, and we collected over $250, so I bought over 125 tickets for the drawing, and we WON! . . . a grand total of $16. But once again, no one won the jackpot that night. By now you know the pattern, so off we went again, this time with $1 Billion at stake; about 40 of us chipped in about $300, and we WON! . . . a grand total of $20, while someone in Michigan purchased the winning numbers. There’s two ways to look at this. It would be easy (and perhaps even accurate) to say a group of 30-40 suckers pooled their resources together for the privilege of turning about $800 into twenty bucks. I look at it the second way, because for about ten days, losing that money was one of the best things to happen to me this entire school year. Look, we all know we’re not going to win the lottery. The odds of winning are worse than getting struck by lightning twice. You have a better chance of getting canonized as a saint than you have of winning the lottery. So you don’t go into it looking to get rich; you’re pretty sure you’re just throwing money away. Our group at school threw money away. But for me, at least, it was about the first time this school year that I did. I am mask-wearing, CDC-guideline-following kind of person, so since March of last year, my wife and I haven’t gone out to dinner or a movie. Nor did we sit home ordering items off the internet. I am by no means rich (and even a little poorer after playing the lottery), but I spent less money on lottery tickets over the past two weeks than I would have spent on social engagements in a non-COVID ten months. The question arises, then: If you know you’re not going to win and you know you’re just throwing away your money, why play at all? My answer is simple. For me, playing the lottery is not at all about buying lottery tickets; it’s about renting Hope. We teach in a public school that routinely ignored local health guidelines in order to get kids back in the classroom, and the I’ll let you imagine the results. On top of that, you may recall we had a Presidential election in November, one that stretched WAYYY past November and only got settled this past week. But then, while waiting for that first drawing, my colleagues and I began to think about something different. Seriously, how many conversations have you had in the last five months that weren’t about COVID or politics? The lottery changed our thinking. Knowing we had no chance of winning, we began to dream about winning. We began to ask each other all of the “What would you do?” questions that come with the hope of an influx of cash. And then we didn’t win, so we got to have those conversations for another four days, and then we didn’t win again, and it continued. What I found, in many cases, is how little we might actually need. Most of us had difficulty saying what we might do with A BILLION DOLLARS, but almost all of us could talk about how radically our lives could be changed with a quarter million, or even a hundred thousand, or even less. We didn’t dream about the foolish, millionaire-playboy kind of things (well, except for one of my colleagues in the Social Studies department, who said he would come to school with a case of Modelo and spend the day making snow angels on school grounds, but if you knew him, you’d understand). Most of us dreamt of security. Pay off our mortgages or our school loans, get a more dependable car, put kids through college—that kind of thing. We didn’t yearn for untold millions. (Don’t get me wrong, we would have accepted them, had the ping-pong balls gone our way.) What we really wanted was a little bit less worry about how to make ends meet. We wanted more time with our families and less pressure, and for most of us, that was good enough. There’s a host of conclusions that could be drawn from this, ranging from how pleasant it was to get to know the people I work with a little better, to how unpleasant it is that an advanced society such as ours does not have an advanced social safety net. I could talk about how stressed we are as we shove 25 students into a classroom that isn’t large enough to socially distance while we watch people in other districts begin to get vaccinated. But I don’t want to talk about any of that stuff, because I’ve had a bunch of those conversations already. Instead, I just wish to express gratitude to the teacher in the classroom next to mine who suggested I start a lottery group. It snapped me out of myself. It gave me something to look forward to. And it proved that money can, in fact, buy happiness, if you approach it with the proper point of view.  If you’re like me, you may recall Chicken Little from stories told to you in your childhood. Some of you may know it as Henny Penny, but the basic idea is the same. Chicken Little was out for a walk when struck on the head with an acorn that dropped from a tree. Panicked, Chicken Little began to tell anyone he could, “The sky is falling!” This gloom-and-doom forecast was of course not true, but Chicken Little managed to instill panic into Henny Penny and Goosey Loosey and Turkey Lurkey and a host of others before the story was done. I am reminded of Chicken Little this week, because I teach in the public schools, and we are coming to the end of our first semester. And we need to talk about how badly it’s going. We need to discuss the fact that the very fabric of life as we know it is falling apart, and that a disaster of epic—and perhaps even Biblical—proportions is coming toward us at full speed. Maybe you’re already aware, but perhaps I am the first to warn you: Our Students Are Falling Behind! As background to this disaster: Last March, a number of schools in the nation shut down as part of an effort to shelter in place to combat the spread of coronavirus. For my school district, that happened on Friday, March 13 (cue ominous music). Teachers in my district were given five days to overhaul our curriculum into an online format so that we might begin online instruction on Wednesday, March 18, with the goal of coming back to school in person during the first week of April. Strike that; during mid-April. Strike that; by May 1. Not that, either. As it turned out, we were not going to come back to school in person for the remainder of the school year, so what began as a two-week stopgap measure became “virtual school.” Then came fall. Here, results vary, but most districts chose one of three options:

Our Students Are Falling Behind! This is bad, if you didn’t know. For students, it means they are missing out on vital lessons that will prepare them for life in the 21st century. For teachers, it means the evaluations they receive for efficacy will show they are less effective; that can get them disciplined, and even fired. For parents, it means their children lag behind their global competition, so it’s possible someone from Finland or China or Mexico might be coming for their child’s future jobs. And for administrators, too many failing students means one could be labeled a failing school, and that can lead to disciplinary actions, firings, or—worst of all—reduction in funding. And kids are failing. We have more failing grades than ever before. We have statistical evidence and we have anecdotal evidence. We have spreadsheets. We have charts. Put it all together, and we have the single most powerful force in education today: we have “Data.” You can’t beat Data. Data has let many a district go full “Moneyball” on their young people. (If you’re unfamiliar with how that works, think of public education as baseball. Data shows us who is going to hit the most home runs, and who strikes out the most. Once a district has identified the lowest quartile of batting averages, it can give directives to raise those batting averages. It rarely provides the actual means to raise those batting averages—for example, hiring more teachers which makes for smaller class sizes and more personalized approaches to “batting practice”—providing the directive is enough. With a directive but without the means, the teacher is left to fend for her/himself, and if it goes poorly, a child’s low batting average is therefore the teacher’s fault; the district can conclude that batting averages didn’t rise because the district had the wrong coach. The end result is that far more districts care less about the Home Run Champions and far more about how many batters get on base, even if they get there with a walk, or—God forbid—are hit by a pitch.) But I digress. The main point is that this data is crystal clear. It says: Our Students Are Falling Behind! Some students, it turns out, don’t learn well in the virtual model. Some don’t learn well in the hybrid model. It turns out that part of student learning might be very closely tied to being in school, but in a COVID paradox, coming to school strongly increases the chances of being sent home and into quarantine as students contract the coronavirus. That, in turn, means those students will end up having to learn virtually for a good portion of the year. On top of that, a lot of the students are stressed. Maybe they don’t learn as well in the new format but their parents want them to get the same grades anyway. Maybe they have to come back to school full-time because it’s open, but they’re terrified while they are there. Some of this fear is a little morbid. Every time the phone rings in my classroom, the students start a betting pool as to who is going to have to be sent home next. A certain gallows humor emerges whenever the principal or assistant principal knocks on the classroom door, looks through the window, and gives a teacher the “come here, please” sign. But some of this fear is just plain fear. Some kids are scared of getting sick. Some are scared of getting others sick. Some are scared because their best friend is quarantined for two weeks and now they don’t have anyone to eat lunch with. Some are scared because their parent’s restaurant is losing money because fewer people are going to eat, or their parents are fighting more, or their grandmother seems to be coughing a lot. And of course, some aren’t scared at all. Some think the virus is a hoax, that masks are a violation of their personal freedoms, and they will work to take their off or let it fall below their nose—or below their chin—whenever they please. Which only scares other kids more, because they view the non-mask-wearers as ignorant petri dishes just waiting to infect the entire classroom with a virus, or with ignorance, or both. What I mean to say is that Our Students Are Falling Behind! because that’s normal. Some students haven’t been inside of a classroom in 10 months. Some have gone from five days of instruction to two or three. Some have tried to be there all five days, but have been unable to do so because of quarantines. But whichever model is in play, students are doing their best in the midst of a global pandemic that has claimed the lives of more than 400,000 Americans, as of this writing, and there are far more important things going on than their grades. In spite of all of that, last week I assigned them Friedrich the Great’s “Essay on the Forms of Government,” and we talked for almost an hour about what government is supposed to do, and be. We talked about reasons for taxation and why punishment needs to fit the crime, and what can be done with the poor, and reasons to maintain a military, and I’m here to tell you: These kids aced it. (And rest easy, data people; everyone passed, and not because I wanted them all to get on base, but because everyone deserved it.) And today, when I had a class of three students because a quarter of our school population was quarantined, and then a class of two students for the same reason, we just talked. We could have talked about the Reign of Terror and its effect on France, but instead we talked about why I became a teacher. We talked about the importance of creating a mixed tape when trying to pick up girls in the late 80’s and early 90’s. We talked about my favorite class in high school and about their favorite class in high school, and why grades were or weren’t important, and what they hoped to do in future years, and how much we all really, really wanted to get vaccinated. The moral of this story is both simple and true: The sky isn’t falling, and the kids are all right. If they’re behind, so what? Teachers meet students where they are. We teach the ones who are behind, and we teach the ones who are ahead, and we do that in person, or virtually, or sometimes through the mail. Just get out of the way and let us teach, and the students will learn. That’s the whole reason we show up in the morning. The kids are all right. No one from Finland is going to show up to steal their babysitting gig or their after-school job at Culver’s, because their bosses at those jobs value flexibility, and the ability to think on their feet, and the ability to keep working even when faced with really hard challenges. And all of those things are things students have learned by trying to go to school in a pandemic. And you know what? The schools are all right, too. They’re doing what they always do, but now they’re doing it in three different schedules with routine absences among the student body and the threat of illness lurking everywhere. On top of that, they’re organizing food pantries and sending meals home for families and providing free laptops, and they’re doing all those things for the masked and unmasked alike. So let’s give schools a break. They’re not failing; the social safety net is. I don’t know when this virus will go away, and neither do you. But it will go away, and if on that day students’ test scores are a little lower, on average, maybe we can give the young people credit for everything they’ve endured instead of listing the ways they came up short. Maybe we can remember that these are human beings we’re talking about, and not batting averages, and treat them as such. So ease up, Chicken Little. The sky isn’t falling. The sky’s the limit. I work with young people every day, and they’re amazing; if you let them, they’ll amaze you, too.  Today is January 19, 2021, which among other things makes it the last full day of the Trump presidency. Tomorrow will mark the one-week anniversary of President Trump’s second impeachment, and the two-week anniversary of the Capitol Riot, when President Trump incited his supporters to attack the United States Capitol Building and the members of Congress and the Vice President inside of it. Since that riot, and since that impeachment, and especially on the eve of the inauguration of Joe Biden as the 46th President of the United States, Trump supporters have cried that Trump critics are being too hard on the 45th President of the United States. Now is not the time for impeachment, they said; it’s a time for unity and healing. Now is not the time to prosecute the rioters at the Capitol Building; it’s a time for unity and healing. No, it’s not. There will be a time for unity and healing, and quite frankly, I hope it’s soon. But we’re not quite there yet, and part of the reason we’re not is that we still don’t have answers to a few questions. For instance: Where’s the wall? You remember the wall, or should I say, The Wall. Candidate Trump promised his supporters—and by extension, the rest of America—that if elected, he would ensure there was a wall running along the entire length of the border separating the United States from Mexico. Not only that; he was so clever that in addition to getting this wall built, he was going to get Mexico to pay for it. It’s OK if you don’t remember, because candidate Trump made a host of promises, and it was hard to keep them all straight. He was going to get rid of the deficit. He was going to overturn Obamacare. He was going to create a fund for infrastructure, starting with a promise of $550 billion to repair America’s roads and bridges. He was going to be a busy guy—so busy that he would never have time to play golf. Of all the things he promised, the wall is the one that stands out in my mind. Part of why it stands out is how ludicrous it was. Honestly, building a wall between the U.S. and Mexico was a really stupid idea to begin with, and the idea that Mexico would pay for it was ridiculous. But when I think about the wall, I remember how candidate Trump’s base just ate that idea up. I mean, they believed, and because candidate Trump wanted this, they wanted it, too. Because candidate Trump showed them it was OK to be xenophobic if not outright racist, his base decided they could be those things, too. And since he was smug, they took smugness to a new level; they took so many opportunities to denigrate the “snowflakes” and the “libtards,” to mock those who were different, all because their leader showed them it was perfectly acceptable to behave that way. So when Trump supporters ask for unity and healing, I have questions. Are you still xenophobic? Might you be racist? Do you still mock those who are different? Do Black Lives Matter? Do Blue Lives Matter, when your side engaged in violence that harmed—and even killed—members of the Capitol Police? And where’s the wall? Have you finally realized just how often he lied to you? Do you understand that you were used? There is no wall. There is no infrastructure fund. Obamacare is still here. He never banned foreign lobbyists from contributing to US elections. He never achieved 6 weeks of guaranteed paid leave. He never had a plan for coronavirus. Operation Warp Speed is slow. He played a lot of golf. And then turned his base loose in an attack on the United States Congress. And now. . . Now, when you think you have a better idea of who he really is—now you want unity and healing. No. Not yet. And here’s why. Many of us who were never Trump supporters have always been kind of amazed at you who were. We wondered why you couldn’t see what we saw. Then we wondered if you did see what we saw, and decided to follow him anyway, which makes us wonder how well we know you. We’ve spent a good part of the past four years wondering if you were duped or if you were serious, and we still don’t have a good answer. We still like you—most of you—but we wonder just how far we can trust you, because we saw what happened to you when candidate Trump came on the scene and started spouting his nonsense, and what happened almost cost us American democracy. And what did you do all that for? Really—was it just to briefly experience a sense of superiority? Were you in it for the hats? Four years ago, you helped elect a con man, who then did what he does best. He conned. He blustered. He lied. He led his supporters—many of whom professed to be good Christians—on a path of slow but steady moral decay. He weakened America even as he shouted about American exceptionalism. You say you want unity. So do I. You want healing. Me, too. But first, I want you to admit you were suckered; I want you to say, in public, “He never cared about me; he only cared about himself.” And then I want you to apologize, on behalf of the tyrant you elected, because we both know he never will. Then I will start to give you unity and healing. Because then I will begin to trust you again.  A funny thing happened to me as the calendar flipped from December of last year to January of this year: I lost my parking spot. I should rephrase that: I didn’t lose “my” parking spot, because I don’t really have a parking spot. The spot I usually used didn’t have my name on it. I wasn’t assigned a numbered space and told, “you park in spot #47,” or anything like that. What I did have is a parking spot I chose in August of last year. A certain degree of thought goes into choosing a parking spot. Some people like to be as close to their chosen building entrance as possible, and some people like to park far away to get their steps. Some like to park next to others they know, to facilitate conversation at the beginning or end of the shift. Others like to park with few cars around them, either for privacy or fear that another car door might open and nick their paint. I compromised. I chose my spot in the second row, but furthest from the entrance (while I don’t believe I will lose 30 pounds that way, I am a person who could benefit from getting their steps). It ended up being far enough away that few parked right next to me, but in a row that is still relatively close to the building; because of the latter, I could walk out with a coworker or two if our schedules aligned. It seemed like a good place. I liked it. From August Inservice to Winter Break, I parked in the same place every day. When school started up again on January 4, someone was in my parking spot. I’m not going to mention names. But there are only about 3-4 people who get to work earlier than I do, so you can be sure I know exactly who took my parking spot. From August to Winter Break, this person parked at the very end of the front row, almost directly in front of me. I don’t know what happened, but on my first day back from Winter Break, they abandoned the front row and chose my spot in the second row. And I’ll tell you, I was lost. I had come to depend on that parking spot. I always parked in that parking spot. So I felt a little miffed that I had been put out, but I also worried, as well; because I always had the same parking spot, I had never paid close attention to where everybody else parked. Now, I had to choose a new parking spot. Obviously, the person who took my parking spot didn’t concern themselves with whether or not someone would be put out, but I was very concerned, because I was going to have to park somewhere else and didn’t know if I would be taking someone else's spot. I parked next to a buddy of mine in the back row, but I was almost certain I was taking someone else’s spot, and even if I wasn’t, I didn’t want to feel like a joiner. So the next day, I just sort of picked one at random, but it seemed too easy; if it was easy for me, it was almost certainly easy for someone else, and I imagined I was taking that someone's spot. So on a break during my second day of wayward parking, I looked out the window and examined the parking lot. There was an entire area that seemed vacant, the far end of the sixth and seventh rows; the next day, I took the last spot in the seventh row, and remained there for Thursday and Friday. Somewhere in that stretch, my assistant principal caught me in the hall and pulled me into her office, saying she needed to talk to me. “Brehm, what’s up with the parking?” she asked. “I always park three down from you--why aren't you in your spot?” That opened my eyes a bit. I wasn’t the only one affected by this; it turns out others had been thrown off, as well! Should I say something? Should I call out the person who took my spot and demand its return? I know it isn’t “mine,” but others had acknowledged it as such, and not just me! I did nothing. One parking spot more or less doesn’t really make much of a difference. But it got me thinking. When it comes to parking, there’s a bit of a Social Contract in place. No one really set it in place, but it’s there. We choose our parking, and most of the rest of us come to accept our parking, and eventually we tacitly agree, this is how we will park. For the good of the group and to keep a certain order within this tiny subset of society, we come together to observe these “rules.” Well. Some of us do. Please understand: this post is not designed to lash out at the person who now parks where I used to park, it's designed to show a certain manner of thinking. When I was displaced, I agonized about not upsetting someone else, but the person who displaced me didn’t give it a second thought. Why should they? After all, they didn’t do anything wrong; the space was not assigned to me, except through the unspoken parking lot Social Contract. They were perfectly free to park where they wished, and they did. But to me, this illustrates a larger point. We like to talk about the freedoms this nation of ours provides, and that’s a worthy conversation. But the manner in which we apply those freedoms varies. There are some, like me, who enjoy the exercise of certain freedoms, but I worry about how my freedoms might affect others. The person who now parks where I used to park isn’t malicious—I really don’t think this person cackles wickedly when pulling in and thinks, “Let’s see how Brehm likes this!”—this person just exercised a freedom without worrying how it might affect other people. They weren't out to get me; they just didn't think about me. Lately, though, I've come to worry about those who are malicious in their exercise of freedom, who perhaps are out to get me, who seem to believe their freedom means they don't have to care about me at all--or you--that they are free to do to us as they will. We’ve just begun the study of the French Revolution in my AP European History class, and today we had a discussion about The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. A student brought up Article 4 of that document, which states: 4. Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else; hence the exercise of the natural rights of each man has no limits except those which assure to the other members of the society the enjoyment of the same rights. These limits can only be determined by law. And for a while, I was pretty good: I talked about how everyone in the room has the absolute freedom to throw a punch, but that freedom ends at the tip of someone else’s nose. And then I couldn’t help myself: “How does Article 4 apply to those in America who don’t want to wear masks?” Do we have the freedom to get ourselves sick? Absolutely. Does that mean we have the freedom to get someone else sick? And how—if we don’t know if we’re sick or not—are we to best exercise the freedom we have in relation to the potential injury we could cause someone else? If the limits are to be determined by law, why can’t we enforce a mask mandate?

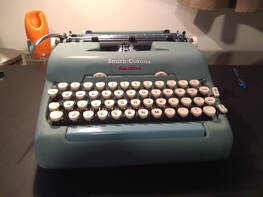

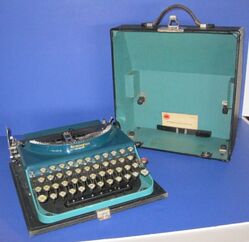

There are a lot of divisions in the nation right now, as any sane reader is no doubt aware, but the one that needs to be fixed soonest, it seems to me, is the one that exists between those with compassion and those without it. This isn’t a Republican/Democrat thing, because I am a registered Neither, and I see those with compassion on both sides. I might suggest those who were involved in the Capitol Riot lack compassion, and I certainly believe that the current President of the United States lacks compassion, as evidenced by how quickly he turned on the very rioters he helped incite. But the vast majority of Republicans I know are decent people who care about others, just like the vast majority of Democrats, and the vast majority of those who don’t vote. The vast majority of Catholics I know have compassion, as do the vast majority of Protestants, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Atheists, and Agnostics. We don’t need a law for this; just a Social Contract. I’ll go forward in compassion, and you’ll go forward in compassion, and then most of us come to expect compassion, and eventually we tacitly agree, this is how we will live. I’ll put my mask on, because I don’t want to get sick, but I also don’t want you to get sick. I’d appreciate it if you would show some compassion and do the same for me. I’ll let you vote, and you let me vote, and if your candidate has more votes than mine, I’ll accept that; I’d appreciate it if—when my candidate has more votes than yours—you’ll do the same. Don’t misunderstand this as a call for unity and healing in regard to the rioters at the Capitol. Those folks broke the Social Contract, and deserve punishment. The President broke the Social Contract, as well, and every day he goes without punishment emboldens others to do likewise. But there are plenty—Republican and Democrat alike—who observe the Social Contract, who wear their masks even when they don’t want to, and who accept that Joe Biden will be the next President of the United States. Those are the people who can exercise their freedoms while respecting the freedoms of others; those folks have compassion for their fellow Americans. This would be helpful in all areas of life, and not just politics. I started with a parking spot. I don’t know how or why the person who parks where I used to park decided to park there, but I don’t really need to know. They parked there, and I chose to be compassionate about that and show concern for their needs, and I found a new parking spot, one that—after all this, I hate to admit it—I kind of like. If you need me, I’ll be at the far end of the seventh row. I could use the steps.  My current machine of choice. My current machine of choice. I have yet to find a great deal of fame or fortune as a writer. (In truth, I don't care about the former, but the latter might be nice.) Still, writing is something that occupies a good deal of my time, so I'm willing to call myself a writer, in the same sense that I occasionally call myself a singer; that is, I am one who writes, and occasionally I am one who sings. Every writer, I imagine, comes up with their own way to write. Some writers don't really write much at all, but rather wait until they are hit with inspiration, and then rush to record it in a single sitting. I am more of a writer who deals in perspiration; if I create something, it usually comes into existence somewhere around the third draft or later. The second and all subsequent drafts happen on a computer, but the first draft almost always begins with my old friend, the typewriter.  A lovely little Smith-Corona. A lovely little Smith-Corona. I love typewriters. Even before I was born, my mother worked in a clerical capacity and learned to type. The first several years of my existence came in a house that also contained a huge black Royal 10. I remember my mother lugging it to the kitchen table and showing me the keys. You had to work to type on that monster; as a kid I couldn't lift it, and it hurt my fingers to press hard enough to actually make a mark on the page. At that age, my favorite thing about a typewriter was simply listening to it, the ways the keys click-clacked under my mother's graceful fingers, the sound of the bell when she came to the end of a row, the large thunk of the carriage return as she moved on to whatever line was next. My high school offered typing and shorthand classes, and I took both--not because I envisioned a clerical future for myself, but because most of the people who took those classes were girls, and as a young man who had no clue how to meet women, I figured that was as good a place to start as any. I don't know why such statistics stick in my head, but I very clearly remember that at the end of Typing 1 I could type 55 words per minute, and at the end of Shorthand 1, I was clocked at 80 words per minute. (I still wasn't dating anyone.) I took no further training, and eventually abandoned the shorthand entirely. But I kept typing, and my speed improved, and now I'm closer to 80 words a minute there, too, as long as those words contain no numerals; the mystery of the numbers and symbols at the top row of the keyboard were reserved for Typing 2. I can still remember the first typewriter I bought for myself, a Smith-Corona portable, made when Smith-Corona was manufacturing some of the ugliest typewriters known to man. The first picture in this post shows a Smith-Corona Electric of a similar vintage; take away the electric and make it a manual, make the body of it a sort of dark babyshit-brown and put olive green keys on it, and you'll have a mental image of my first typewriter, purchased at a secondhand store for five dollars. It was ugly as sin, but the rise was just perfect, and the clickety-clack was quite soothing, and the bell gave a sharp ding! that let you know it might be old, but that typewriter meant business. I wrote my first short story on that typewriter, and my second and third. I didn't even realize that typewriter was turning me into a writer, nor that it would spark an interest that has never really gone away. I wish I could tell you what happened to that typewriter. I suspect it was merely abandoned, as I was a young man who moved a lot, constantly in search of cheaper housing, since money was a constant lack. With no typewriter, I did no writing, but at the time that was OK, because I was dating, and eventually engaged, and then married. I got a job managing an apartment complex, which gave us a little bit of money and free place to stay, which seemed luxurious after some of the places I had lived. The head of maintenance at that apartment complex had just discovered this new website called eBay; he and his wife spent their weekends going to auctions and secondhand stores, hoping to find things they could sell on eBay for profit, and he asked if my wife and I might like to come along. We had nothing going on, so we did.  I don't own this one; I sold mine to help pay tuition. Anyone got a spare? I don't own this one; I sold mine to help pay tuition. Anyone got a spare? And there it was: A typewriter case, sitting on top of a dusty nightstand, waiting to go under the hammer. I opened the case and saw a drop-dead gorgeous Remington 3 portable, white keys with nickel-plated rims set in a frame of two-tone blue (just like the one in the picture to the left). Comparing it to the babyshit-brown Smith Corona of previous days was like comparing Cinderella at the ball to her ugly stepsisters, and I was every bit as smitten as Prince Charming. After a brief round of bidding, I bought that typewriter for fifteen dollars. And that began a love affair that still hasn't ended. At that time, more and more people were buying personal computers; typewriters were things of the past, and could be procured relatively cheaply, and I soon came to a place where I owned 90 of them. My wife and I eventually moved out of our rent-free apartment and bought our first house, and one entire room was dedicated to typewriters. Some I used (I was writing again) and some I just looked at; I could have done that for quite some time, except that I had decided it was time to stop having jobs and start having a career. I wanted to go back to school to become a Social Studies Teacher. Doing so would mean I would have drop down to part-time work, which meant I would have to come up with some money from somewhere. I had a weird-looking, huge old standard typewriter with "Daugherty Visible" written across the top. It was old; so old, it sat on a wooden board, and the case that came down over the top of it was solid metal. I had found it in an antique store, buried under some other stuff in the back corner (pro tip to typewriter hunters; they're heavy, so they tend to be on the floor), and paid fifteen dollars for it. It didn't work, or didn't work well; I had only bought it because I hadn't seen a typewriter quite like it, and it was cheap. But I needed money, and it took up a lot of space, so I took some photos of it and put it on eBay, just to see what would happen. What happened was that seven days later the auction was complete, and I sold it to a guy in Germany for over a thousand dollars. It turned out, I had been ahead of the curve, and typewriters were now collectibles. If you're curious, shipping typewriters is a colossal pain in the ass. Just finding boxes big enough is a challenge, and then you need enough bubble wrap and packing peanuts to make sure it mostly arrives in one piece. Then you lug it to the post office or a shipping company, where you discover the sheer weight of it makes for an expensive package. Still, that was what I did, over and over again, selling almost everything, including the two-toned blue Remington 3 that had started the collection. Typewriters, therefore, made me what I am today; I made enough money selling that collection (and pinching pennies everywhere else) to complete my teaching degree, which has been my livelihood ever since. And, now that I'm fifteen years into a teaching career, I'm writing a lot more. My typewriter collection began again, once I had enough money saved up. It's a smaller collection, and it ebbs and flows. A number of my former students have shown interest in my typewriters, and several have therefore become gifts; it's always good to spread dorky joy whenever you can. As it stands, I think I have about 35 (some are in the storage unit, so an exact count is impossible at this moment). I don't own anything too valuable or extravagant, because I'm not really a typewriter collector as much as I am a writer. I want a machine that is ready to go to work, and not just one that looks pretty on a shelf.  Someday, perhaps some of that writing will reach a broader audience. Someday, I'll post about typewriters again, and explain why all of my first drafts happen that way. Mostly, as I age, I find I miss the sound of a typewriter in another room, just as I miss the mother who used to type on it. All hobbies are screwy to those who don't share them, but this hobby is mine, and my life has been better for it. If you think you'd like to try it, let me know, because I probably have a few typewriters I could bear to part with, and dorky joy is still joy. Thanks for reading.  A Hero, To Many Young People. But Heroes Fall. A Hero, To Many Young People. But Heroes Fall. Heroes are tricky. Almost all of us have been guilty of hero worship to some degree or another. My heroes tend to be writers like Neil Gaiman or activists like Rosa Parks, or those blessed few who can be both, like James Baldwin. But even then, my hero worship is pretty low-key. I might want to be as involved as Rosa Parks, but I don't have a shrine to her in my house; I certainly wish I could write as well as Neil Gaiman, but I wouldn't pay $300 for a pair of his old socks. My best friend gets far more serious about his hero worship. I can still remember his admiration for Lance Armstrong, back in the day. He read books about Lance Armstrong, and books by Lance Armstrong. He watched films about Lance Armstrong, taped the Tour de France so he could keep up with Lance Armstrong on each leg of the race. He even signed up for a charity event and became one of a couple thousand people who once took a bike ride with Lance Armstrong. And when he found out Lance Armstrong cheated, it was a blow to his system. Heroes are tricky, because sometimes they fall. I say all this because -- if you haven't already figured it out -- I am, by profession, a public school teacher. Specifically, I teach high school Social Studies, which means that after the events yesterday at the U.S. Capitol, I got to hang out with school-age young people today as they processed what went on there. Some were outraged, as you might imagine. Some, of course, had no idea what had transpired because politics is B-O-R-I-N-G. But a number of them ranged from a bit put out to downright shell-shocked. Between myself and some of my colleagues, here's a brief sample of some of the things we heard:

A number of yesterday's outcomes were negative. People lost their lives. Federal property was destroyed. The democratic process was delayed (though not overcome). But I have to wonder if the President considered what the outcome would be for some school-age children, who finally found out he was not as popular as they had been told, who finally saw through messages that had been fed to them by a biased media, who finally recognized that even their heroes could go too far. It's said that lessons like these are part of building character, and since almost any experience helps build character, I suppose that's true. But a lot of young people had a painful lesson in growing up today, and as someone who was in the building with them, that wasn't easy to see. No one likes watching dreams die, and young people should remain young as long as they possibly can. |

AuthorE. M. Brehm Archives

January 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed